All posts

All posts

February 9, 2026

All posts

Prior Authorization

February 19, 2026

Prior authorization was designed to ensure medical necessity and appropriate use of healthcare resources. A simple concept: before delivering care, confirm it meets clinical guidelines and coverage criteria. In theory, PA protects patients from unnecessary procedures and payers from inappropriate claims.

In practice, prior authorization has become healthcare's most universally despised administrative process.

Physicians complete an average of 39 prior authorizations per week, spending 13 hours on the process. They navigate multiple payer portals, each with different requirements and interfaces. Ninety-three percent of physicians report that PA delays patient care, while 94% say it negatively impacts clinical outcomes. More than one in four physicians (29%) reported that prior authorization has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care.

Here's what nearly everyone gets wrong: they think prior authorization failed because it's fundamentally flawed, or because stakeholders have competing interests, or because regulations haven't kept up.

The real failure is architectural. Prior authorization collapsed under the dual pressures of fragmentation and scale, and every attempt to fix one problem made the other worse. Payers and providers built disconnected systems to handle growing volume, creating fragmentation. Then they tried to scale those fragmented systems with more tools, more staff, and more workarounds, creating more fragmentation.

Understanding this cycle is essential to evaluating solutions. Because if you don't understand why PA broke, you can't identify what will fix it.

Prior authorization didn't start as bureaucratic quicksand. It began as a practical solution to a specific problem: spiraling hospital costs following the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.

Before the 1960s, physicians prescribed treatments without external review. But as insurance coverage expanded and medical technology advanced, hospital admissions surged and healthcare costs exploded. By the early 1960s, more than 60 Blue Cross plans had already begun reviewing claims for "medical necessity," requiring physicians to justify continued hospitalization after a set number of days.

These early utilization reviews introduced a radical idea: payers could require approval before care was delivered. The 1973 Health Maintenance Organization Act formalized this approach, cementing prior authorization as standard practice.

But in its early years, the process was remarkably simple:

This simplicity worked because the system was small. Prior authorization touched a fraction of healthcare services. The same standards applied across limited scenarios. Everyone spoke the same clinical language.

But this unified, manageable system contained the seeds of its own destruction: it couldn't scale. As PA expanded beyond hospital stays to outpatient procedures, diagnostic tests, and eventually medications, the volume overwhelmed the simple phone-call-and-decision model. What worked for reviewing 50 hospital admissions per week couldn't handle 5,000 authorization requests across dozens of service types and hundreds of payers.

Prior authorization had to evolve, and the way stakeholders chose would determine whether PA became more efficient or more fragmented.

The managed care revolution of the 1990s shattered prior authorization's unified foundation.

HMO enrollment exploded from 36.5 million in 1990 to 58.2 million in 1995. By mid-decade, the majority of Americans with employer-based insurance were enrolled in some form of managed care plan. Prior authorization, once limited to hospital stays and rare expensive procedures, expanded across the healthcare spectrum.

The volume exploded. Outpatient services, diagnostic tests, specialist referrals, and medications all began requiring approval– what had been dozens of hospital admission reviews per week became thousands of authorization requests across multiple specialties, procedures, and medications.

Facing this surge, payers and providers made a choice: each would build their own systems to handle PA at scale.

Payers built proprietary portals. UnitedHealthcare created its systems. Aetna built different ones. Blue Cross Blue Shield plans– each independent– developed their own platforms. Every payer implemented unique requirements, forms, and processes. What qualified as medical necessity for one payer, may not have for the next. Documentation requirements varied. Even submission channels differed– some accepted faxes, others required phone calls, others demanded portal submissions.

Providers, meanwhile, built their own infrastructure to navigate this proliferation. They hired staff dedicated solely to prior authorization. They created internal databases to track which procedures required PA from which payers. They trained teams to manage multiple payer portals, each with different login credentials, interfaces, and workflows.

The scale problem had seemingly been solved: both sides could handle higher volumes. But fragmentation emerged as the unintended consequence. Providers now needed to navigate dozens of disconnected payer portals, spending hours determining PA requirements that differed by payer, by plan, and sometimes by region. A single health system might need to manage authorizations across 50+ payer portals, each with its own rules.

Even when technology advanced, fragmentation persisted. HIPAA's 1996 Administrative Simplification provisions established electronic data interchange standards, promising to streamline PA through a standardized transaction format (the X12-278). But as of 2022– over 25 years later– only 28% of medical prior authorizations moved through this electronic standard. The rest still relied on faxes, phone calls, and payer-specific web portals.

Hiring more staff didn't solve the problem, it just multiplied the chaos. Adding authorization specialists meant training them on more disconnected systems, managing more payer-specific workflows, and coordinating more handoffs across fragmented processes. Scale increased, but so did complexity.

The 1990s taught healthcare a lesson it would struggle to unlearn. Building independent systems to solve volume problems produces fragmented infrastructure.

Fragmented infrastructure compounds with growth: more handoffs, more training, more failure points. Worse, it makes future scaling structurally impossible.

The 2010s brought a wave of optimism. Prior authorization technology vendors promised to solve the scale problem through automation. CoverMyMeds launched in 2008. Surescripts expanded into electronic PA. Dozens of specialized vendors emerged, each offering software to streamline workflows, reduce manual work, and accelerate approvals.

The pitch was compelling: automation would eliminate the administrative burden that fragmentation had created. Electronic systems would replace faxes and phone calls. Smart software would handle the complexity.

But point solutions didn't eliminate fragmentation. They added to it.

Most automation tools operated as standalone systems. They didn't connect deeply to EHRs: clinical data still required manual entry. They didn't integrate with payer systems: submissions still went through portals, faxes, or phone calls. Staff now logged into PA software, extracted data from the EHR, submitted through the vendor's platform, then tracked status in yet another interface.

Each tool created its own database, its own workflow, its own training requirements. As of 2022, many ePA solutions still lacked integration with diverse EHR systems, necessitating redundant data entry and manual follow-ups. Providers using multiple point solutions– which became necessary to cover different specialties or payer networks– found themselves managing even more disconnected systems than before.

The compounding effect became clear. More automation tools meant more data silos. More interfaces meant more manual handoffs between systems. More vendors meant more integration projects, more contracts, more points of failure.

Worse, point solutions optimized for specific workflows often broke when applied across different specialties or care settings. Providers needed different solutions for different service lines, multiplying the fragmentation problem.

Some vendors achieved better integration—connecting to hundreds of EHRs and covering broad payer networks. But even these faced a fundamental limitation: they automated within fragmented infrastructure, not across it. The underlying architecture– disconnected payer portals, specialty-specific requirements, inconsistent data standards– remained unchanged.

By the late 2010s, a paradox emerged. Healthcare had more PA automation than ever before, yet the administrative burden continued to rise. Physicians completing 39 PAs per week spent 13 hours on the process. The technology existed. The fragmentation persisted.

When point solutions proved insufficient, health systems took a different approach: build it themselves.

The logic was sound. No off-the-shelf tool could handle each organization's specific combination of payers, specialties, and workflows. So providers built internally. Dedicated authorization teams, custom spreadsheets tracking payer requirements, processes stitched together from EHR modules, vendor tools, and manual steps tailored to each facility.

This became a dominant strategy. By the mid-2010s, 40% of practices employed staff dedicated entirely to prior authorization. Despite massive EHR investments, most PA work still happened outside those systems– through manual workarounds, phone calls, and faxes. Eighty percent of prior authorization submissions and verifications remained manual.

Every organization's solution was unique. Implementation experts working across health systems consistently find that no two prior authorization workflows look the same, not across organizations, and often not even across departments within the same facility.

This felt responsive. It was also a trap.

Custom workflows are built by individuals with deep knowledge of specific payer landscapes. When those individuals leave, the knowledge leaves with them. Every new payer requires rebuilding. Every new specialty requires a parallel workflow. Every new facility requires duplicating and re-customizing the entire operation.

The build-it-yourself era added a third layer of fragmentation. Payers had created disconnected portals. Point solutions had introduced isolated automation tools. Now each health system had layered on its own custom processes– unique, untransferable, and increasingly unmaintainable at scale.

Every era in prior authorization's history followed the same pattern: A scaling challenge appeared, stakeholders responded with a structural solution, and that solution introduced new fragmentation. The new fragmentation created the next scaling challenge.

This wasn't a coincidence. Fragmentation and scale are locked together. Each one feeds the other, and understanding how is the key to understanding why prior authorization has resisted every fix thrown at it.

Fragmentation prevents scale in four specific ways:

But the cycle runs in both directions. Scaling also creates fragmentation. Adding facilities means replicating disconnected systems across new locations. Adding specialties means building entirely parallel workflows, because no existing process was designed to accommodate them. Adding staff means training each person on the full constellation of fragmented tools. Adding payers means adding more disconnected portals to the landscape.

This is the cycle that has defined prior authorization for almost forty years. Each attempt to scale required building more infrastructure, each new infrastructure introduced more fragmentation, more fragmentation demanded more effort to scale. The system got bigger, but never simpler.

Thirty-five years of prior authorization history converge on a single conclusion: fragmentation and scale cannot coexist. Any architecture that treats them as separate problems will fail. The path forward requires solving them simultaneously: building infrastructure that is unified by design and scalable by nature.

That is a harder problem than it sounds. The instinct in healthcare is to patch. More tools. More staff. More workarounds. Each addition was a rational response to an immediate pressure. But each addition made the underlying architecture more complex, more brittle, and harder to change. Breaking the cycle means resisting that instinct entirely.

Unified, scale-ready prior authorization starts with connectivity as the foundation, not an add-on. Clinical data flows directly from the EHR into the authorization process without manual re-entry. Submissions reach payers through direct integrations, not through a patchwork of portals and fax lines. Status updates return automatically, in real time. Every handoff that currently requires a human becomes a data flow.

It requires intelligence at the point of decision. PA failures happen at predictable moments: when documentation doesn't match payer criteria, when submissions go out incomplete. AI can intervene before submission, not after denial– matching documentation to policy requirements and identifying gaps before they become rejected claims.

It demands a single workflow across specialties, facilities, and payers. Not parallel processes rebuilt for each new service line. One architecture that adapts to different requirements without fragmenting into different systems.

And it requires shared visibility across the entire authorization lifecycle, from order to outcome. Not just for providers– for payers, too. Shared data, shared infrastructure, both sides working toward the same goal.

These capabilities exist today. But they only deliver results when built together, from the ground up, as an integrated system, not assembled from disconnected pieces after the fact. That distinction– purpose-built versus stitched together– is the difference between an architecture that scales and one that fragments.

The decision to adopt a prior authorization solution is an architectural one. The question is not just whether a tool automates submissions or tracks status, but whether it was built to unify– or whether it was built to fit inside a system that is already fragmented.

For three decades, healthcare has chosen the latter. The cost of that choice is measured in denied claims, delayed care, and billions in administrative waste.

Humata was built from day one with that architecture in mind. Because when prior authorization moves forward, care can move forward.

Allegheny Health Network Partnered with Humata to Centralize & Automate 200,000+ Annual Prior Authorizations

Prior Authorization

Provider

Technology

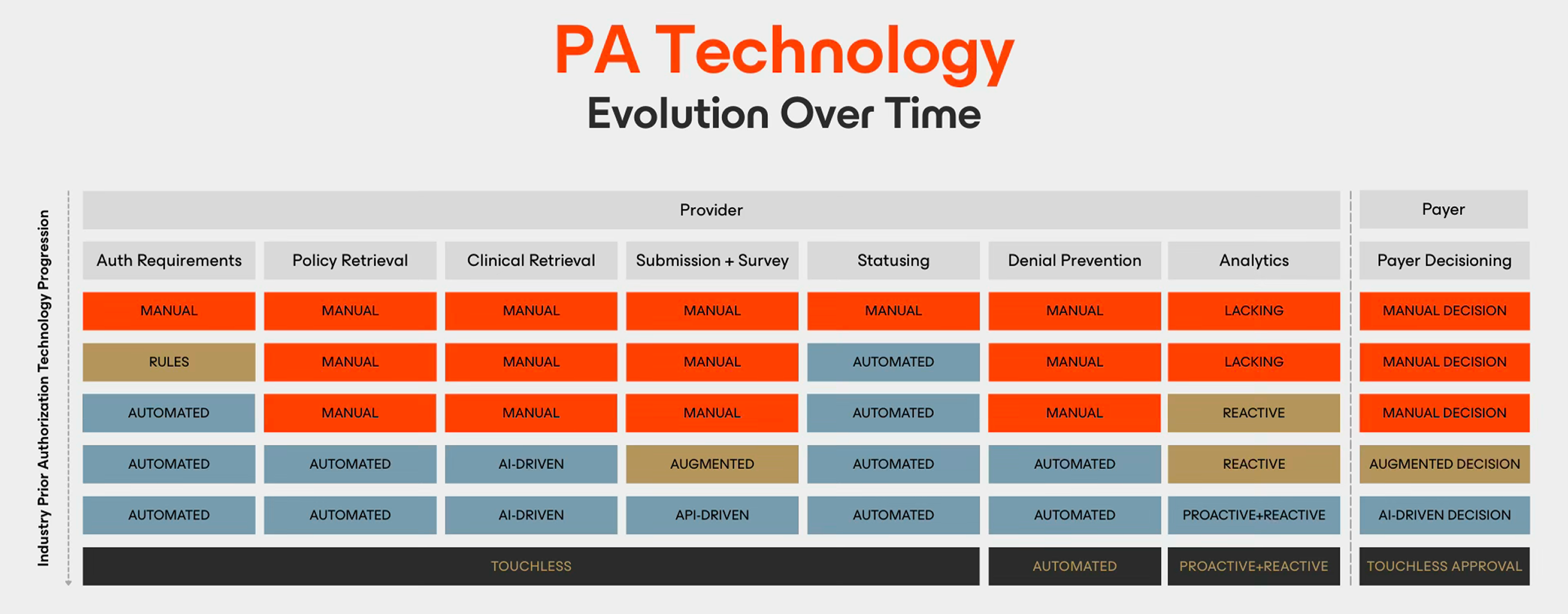

Why Prior Authorization Technology is Harder Than It Looks

Prior Authorization

Technology

Provider

Prior Authorization Terminology: A Complete Guide

Prior Authorization